Reviving the memories of young Hideki Yukawa

I was astonished when I was examining the huge quantity of the historical materials of Hideki Yukawa.

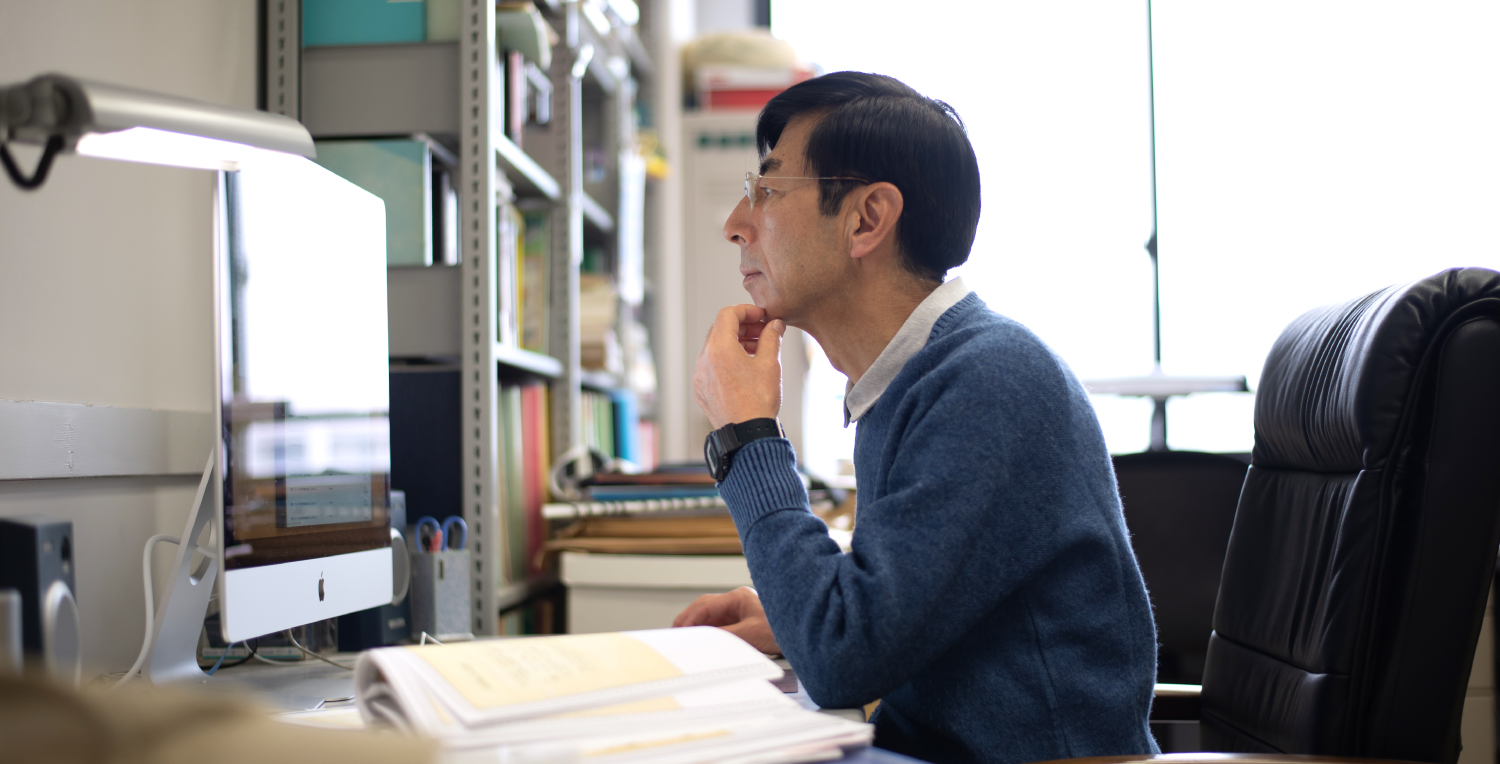

Yukawa was awe-inspiring during his years at Osaka Imperial University. My recognition and image of Yukawa changed completely. Yukawa strove to unravel the threads of mysteries based on experimental and observational facts. He worked assiduously to formulate his original theories and conducted research together with his colleagues. I respect him as a great researcher and have a sense of affinity with him as a researcher in the same field of study.

|

Q: When did you meet Hideki Yukawa? I remember reading about Hideki Yukawa being the first Japanese to win a Nobel Prize in one of the books titled “The Stories of the Great Historical Figures.” I got to know a little more about him when I learned physics in the junior high school. I was told then that Dr. Yukawa was a leading physicist who discovered a new particle called a meson. Needless to say, I didn’t know what his theory was about. Nonetheless, I remember the picture of Hideki Yukawa in the school textbook. His eyes in the picture were gleaming as if looking straight toward truth. The picture left a strong impression in me. I was touched. I got to know him better after I started studying physics in the undergraduate school and graduate school. In the university, I heard the term, pi-meson. In the graduate school, I learned that the basic elementary particles were quarks and electrons and that the mechanisms of the weak force and strong force could be understood based on the gauge theory. In other words, it was believed then that the meson theory was inadequate and the gauge theory was considered as the key to understanding truth. To be honest, I thought that the meson theory was an effective theory but not a theory of the future. |

|

|

Q: Then, what happened? After receiving my degree, I got a job at University of Chicago, where I often discussed with Professor Nambu. Professor Nambu had a different view. To unlock the secrets of nature, we physicists seek theories behind natural phenomena and verify them through experiments and observations. In the case of the theory of elementary particles, theorists take one of the two patterns of theorizing to seek the true theory. Professor Nambu explained that there are two modes, the Dirac mode and Yukawa mode. Natural science is advancing constantly. Something new is created at the frontier from time to time. In the era in which Yukawa lived, nobody thought of assuming the existence of new particles for the purpose of explaining the force that acts between the protons and neutrons in the nucleus. Yukawa’s novel and innovative idea was what made Yukawa so prominent. He accomplished something that no other researchers could. I feel that the landscape and origin of Yukawa’s thoughts were remaining in the heart of Professor Nambu. |

|

Q: Does that experience relate to the historical materials of Yukawa? Yes, I think so. First, I would like to mention the following regarding the historical materials of Yukawa. The historical materials of Hideki Yukawa at Osaka Imperial University on display at The University of Osaka are just some of the materials archived and managed by Kyoto University. Yukawa was a very tidy person. He organized and filed in envelopes not only lecture manuscripts and research manuscripts he wrote during his years at Osaka Imperial University but also calculation notes, programs of meetings and colloquia hosted by various academic societies and other organizations, received letters, etc. Those envelopes were found in Kyoto University and are now archived by the university. Other materials and photos were found in the Yukawa Family Residence. Headed by Professor Konuma, the group of Kyoto University members and other concerned people have been archiving them, spending more than 30 years sorting and cataloguing those documents and photos. I would like to thank them sincerely and pay my heartfelt respects.

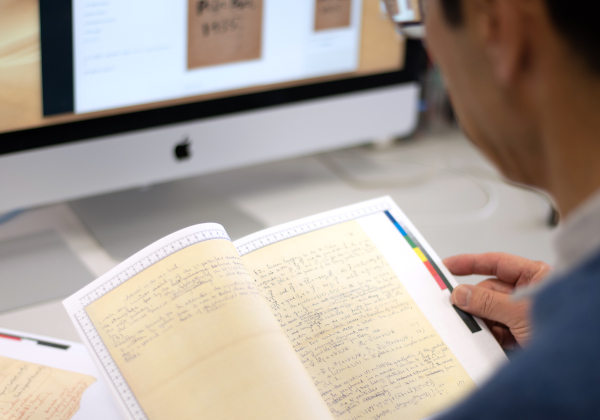

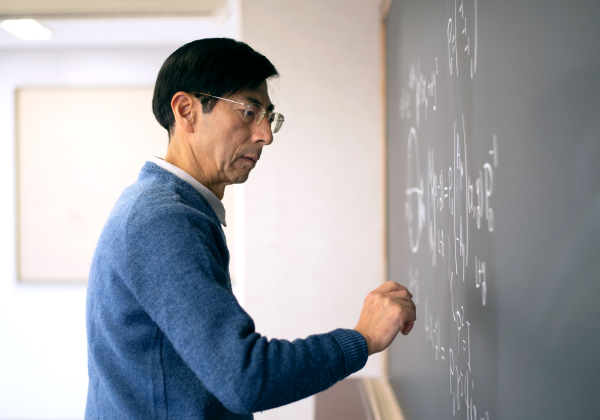

In particular, the historical materials of Yukawa during his years at Osaka Imperial University gave me a big surprise. When I saw them, I felt young Hideki Yukawa reviving in me. Young Hideki Yukawa worked laboriously day in and day out, studying and debating with friends in an effort to gain a better understanding of natural phenomena. He enjoyed learning something new every day and explained the importance of physical properties and statistical mechanics based on quantum mechanics to the people in the Department of Physics. He did not even take a rest from his writing of report or research paper. The Osaka Branch of the Physical and Mathematical Society of Japan used to hold a meeting regularly in the lecture room at Osaka Imperial University. The one-sheet mimeographed program shows that Yukawa and his fellow researchers gave lectures that were about 5 to 15 minutes long each. In the calculation notebook, Yukawa jotted down how he intended to explain, for example, the process of the atomic nuclear decay (beta decay) and the kind of nuclear force required for explaining the spectrum of the atomic nucleus in the lecture. These materials show Yukawa’s trial-and-error calculation processes. The graffiti drawn in the blank spaces bring an interesting thought to me. I wonder if Yukawa drew them because he had some free time, because he took a short break, or because his thoughts were at a standstill. Physics theories must be more than just “intriguing.” Ultimately, they must be able to explain the experimental or observational results. I can feel Yukawa’s strong determination through the historical materials. I am sure that the Department of Physics of Osaka Imperial University received substantial influence from the presence of Seishi Kikuchi at the university. |

|

|

|

Q: Can you talk more about the reviving of the memories of young Hideki Yukawa? Dr. Yukawa’s attitude towards research was astonishing. In a sense, that was very normal for him. He believed in studying. Many people started adopting similar attitudes and conducted research together with him. They organized a study group and assigned the members to the studying of the papers (in Germany, English, French, etc.) that were regarded important and then extracted the topics to address. They exchanged ideas and conducted various analyses and calculations. Things did not go smoothly in more cases than not, however. If the research faced a deadlock, someone proposed another idea. When joint research was conducted, the tasks of writing the manuscripts for lectures and reports were divided among the members. For the production of a research paper, Shoichi Sakata and Mitsuo Taketani wrote (wonderful) drafts (summaries) in Japanese, and Hideki Yukawa wrote in English in beautiful handwriting. The corrections he made are also interesting. Hideki Yukawa not only conducted research but also gave lectures on then cutting-edge quantum physics to the physics students and instructor. He carefully prepared notes for his lectures. I admire Dr. Yukawa’s assiduity and meticulousness. Yukawa must have had a firm sense of mission. Yukawa wasn’t always studying. He practiced baseball in the afternoon and went home in Nishinomiya at about 5 o’clock. On the way home, he did some shopping in Umeda. He lived a well-balanced life. Yukawa was a hard worker. He was filled with the ambition to explore a new world. That spirit is called Yukawa Mind. I think Yukawa Mind drew many young people to Osaka. |

|

Q: Did he receive his doctoral degree from Osaka Imperial University? Yes. Many people have misunderstandings about that. Yukawa wrote his first paper (his famous Nobel Prize winning paper written in November 1934) when he was at Osaka Imperial University, and received his doctoral degree (Ph.D.) in 1938 from Osaka Imperial University. In May 1939, he started working at Kyoto Imperial University. Yukawa was a member of Osaka Imperial University from 1933 to May 1939. Why didn’t he obtain a doctoral degree (Ph.D.) until 1938? From 1935 to 1937, Yukawa wrote about 10 papers together with mainly Sakata. His first paper was probably sufficient for obtaining a doctoral degree (Ph.D.), but he might not have been completely satisfied with the paper since there was no experimental evidence (or signs of it) at that time. In fact, in 1936 there were many physicists who did not acknowledge Yukawa’s theory. The turning point was probably brought by Anderson’s discovery of the new particle, which is known as a muon today, in cosmic rays in 1936. At that time, many people thought that the particle discovered by Anderson might be Yukawa’s meson. Yukawa also scrutinized that possibility and wrote a paper. In that document, he pointed out the issues resulting from identifying Anderson’s particle as Yukawa’s meson. Nevertheless, the existence of the new particle was confirmed. Earlier, I mentioned how Professor Nambu regarded Yukawa’s ideas. Yukawa’s idea of introducing a new particle was revolutionary at that time. Until Anderson’s discovery, 99% of physicists considered that the introduction of a new particle was unnecessary and unnatural and disregarded Yukawa’s idea. Anderson’s discovery changed the whole situation. Introduction of the new particle was not readily rejected anymore. Yukawa must have developed confidence in his theory. With that confidence and conviction, he must have written his doctoral thesis and nine reference papers and submitted them together with the application for doctoral degree to Osaka Imperial University.

Q: I see. That is a remarkable story. Yes, indeed. Hideki Yukawa was amazing during his years at Osaka Imperial University. He was a scholar researching in the cutting-edge field of physics. Hideki Yukawa’s spirit remains at The University of Osaka. The historical materials displayed in Yukawa Memorial will revive the memories of young Hideki Yukawa in the mind’s eye of the beholder. (English translation by KSI.) |

|